Our corporate offices and customer solutions center will be closed December 24-25, reopening on December 26.

CCIM Connections

The Official Publication of The CCIM Institute

Image

Fall 2024

Cover Story

Supreme Court Overturns Chevron Doctrine, Reshaping CRE Regulation

Read ArticleImage

The Latest Trending Articles

Featured Articles by Issue

Stay Up to Date on All Issues

Hero image

Intro Text

Bringing Success and Strength to The CCIM Institute

Hero image

Intro Text

Making Deals - Spring 2024

Intro Text

Driving The CCIM Institute's Growth

Hero image

Intro Text

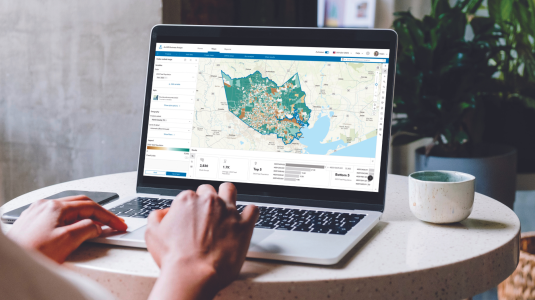

Site To Do Business is commercial real estate's most advanced digital toolkit providing essential data components and marketing tools to give your audience a broader perspective on today's market.